|

Dyslexia in the Classroom

The co-director of the Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity talks about the learning disability and how it affects kids in school.

“Science has made a great deal of progress in understanding dyslexia, but it hasn’t been translated into practice as much as it should be,” according to Sally Shaywitz, MD, co-director of the Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity and a professor in learning development at the Yale University School of Medicine.

We spoke to Dr. Shaywitz about dyslexia, signs parents should look for, and how children with the disability can cope and succeed in school.

There are a lot of misconceptions about dyslexia — that it’s a vision problem as opposed to a language-based learning disability, for instance. What are some of the common mistakes people make about it?

A lot of people think dyslexia means seeing letters and words backwards. It doesn’t. What often happens is a parent sees their child struggling to read, but because they’re not reading backwards they think it can’t be dyslexia.

A common thing people will say is that it’s a developmental lag. It’s not. There have been studies that show that when kids struggle with reading it’s not that they’re slower to do it, it’s that they can’t do it. It’s sad that sometimes people think the child isn’t trying hard enough. Everybody tells their child when they’re starting school that they’re going to love reading, and suddenly the child is lost.

Slow reading should not be confused with slow thinking. Some of the brightest people in our society are dyslexic, people who have won Nobel and Pulitzer prizes.

What are some of the earliest indicators that a child may be dyslexic?

The earliest symptom is a delay in speaking. Because the child has trouble pulling apart the spoken word, they don’t recognize rhymes. How do children enjoy Dr. Seuss? They pull the words apart, like “mad, hat, cat,” and recognize that they rhyme.

As children get a little older, three to five years old, they have trouble recognizing letters, and then linking letters to individual sounds. As they get even older, they have trouble retrieving the word they want to say. A little girl looking at a picture of a volcano might say it’s a “tornado.” She knows what she wants to say, but it’s very hard for her to pull out the sounds to be able to do that.

It’s not a question of knowing the concept. It’s a matter of actually uttering the word. It’s referred to as a word retrieval problem. You can imagine how embarrassing it is to a child in school.

A lot of kids with dyslexia learn how to read relatively accurately, but they don’t read fluently. Fluent reading means you read rapidly and automatically. You see a word and you know it. So reading is pleasurable, and you don’t need to use up your attention to read.

What should parents do if they suspect that their child may have a learning disability?

If you suspect something might be wrong, I would start with the teacher and work your way up to the principal. See if there’s a learning specialist at the school, or maybe the head of special education. A younger child should be assessed by a speech and language pathologist who really knows how to pinpoint the difficulty. There’s no reason to wait, the earlier the better.

Is dyslexia related to other learning disabilities, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder?

There’s a very high co-occurrence of dyslexia and attention disorder. Sometimes the attention disorder will be picked up, and they’ll miss that there’s a reading disorder as well.

When you can’t read automatically, you use up all your attention and effort trying. Those kids in class may look like they’re not paying attention and looking around, so it can be confused with attention disorder. Similarly, the kids with reading disorder often do have attention disorder and it’s missed. So if a child is diagnosed with one, they should be evaluated for the other.

Students with learning disabilities don’t always get the accommodations, such as extended testing time, they’re entitled to. Why, and do they make a significant difference in academic achievement?

Schools sometimes think because a child takes longer on a test that they can’t go on to a higher level subject. The child can understand the concepts and do the work, but they may need extra time on a test. But kids don’t want to ask for extra time — nobody wants to be different.

Children really need to get the extra help, but sadly they often don’t get it in school. For parents who can afford it, kids can work with a tutor when they get home from school.

It’s really important for the child to have time to do something that they enjoy, something that they’re good at and feel good about.

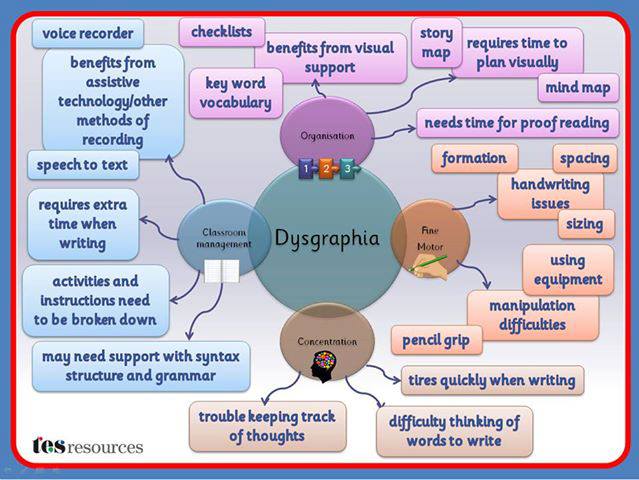

Dysgraphia mind map

Parents Advocating for Student Success in EDucation (PASSED)

Lunch Gathering

Wed. June 26, 2013

Vineyard Church ~ 1533 W. Arrowhead Rd ~ Duluth, MN 5581

This group meets monthly to share ideas and support one another. If your child struggled last year in school this may be a good opportunity to hear what others in our community are doing to ensure their children’s success in learning. Occasionally, a speaker joins the group to cover a specific topic. All families are welcome.

Vineyard Church offers a lunch for $5.00 made by the members of the congregation, or you’re welcome to bring your own. Lunch is served at noon until they run out.

We also have a monthly evening gathering at Barnes and Noble 7PM on Thursday, June 27, 2013 for those that can’t make a noon time.

Our lunch gatherings are usually the third Wednesday of the month (June is an exception) and the evening meetings are usually on the fourth Thursday of the month. Email dwyers@boreal.org if you’d like more information.

Dyslexia: More Than a Score

By Dr. Richard Selznick (http://www.drselz.com/blog)

Saturday, June 8, 2013

***Note: (This blog was published some time ago, but due to a problem with the website it needed to be reposted. It has been revised.)

I had the good fortune to recently take part on a panel during a symposium on dyslexia sponsored by the grassroots parenting group, Decoding Dyslexia: NJ. Dr. Sally Shaywitz, the author of “Overcoming Dyslexia” was the keynote speaker. While talking about assessing dyslexia, Dr. Shaywitz said something that really struck me. She noted, “Dyslexia is not a score.”

That statement is right on the money.

Scores are certainly involved in the assessment of dyslexia. Tests such as the Woodcock Reading Mastery Test, the Tests of Word Reading Efficiency and the Comprehensive Tests of Phonological Processing, among other standardized measures yield reliable and valid standard scores, grade equivalents and percentiles. These scores can be helpful markers. However, the scores often don’t tell the whole story.

Here’s one example:

Jacob, a fifth grader, is in the 80th%ile of verbal intelligence and his nonverbal score is in the 65% percentile, meaning Jacob’s a pretty bright kid. Jacob’s word identification standard score on the Woodcock was a 94 placing him solidly in the average range, with similar word attack and passage comprehensions scores. Effectively, both of the scores (Word Identification and Word Attack), placed Jacob just below the 50th percentile, but solidly in the average range.

Jacob’s scores would not have gotten the school too excited. Yet, here’s what I told the mom.

“There’s a lot of evidence in Jacob’s assessment that suggests that he is dyslexic. Even though his scores are fundamentally average, he was observed to be very inefficient in the way that he read. For example, while Jacob read words like “institute,” and “mechanic” correctly, he did so with a great deal of effort. It was hard for Jacob to figure out the words. For those who are not dyslexic, word reading is smooth and effortless. Those words would be a piece of cake for non-dyslexic fifth graders. They were not for Jacob.”

“Even more to the point, was the way that Jacob read passages out loud. Listening to Jacob read was almost painful. Every time he came upon a large word that was not all that common (such as, hysterical, pedestrian, departure) he hesitated a number of seconds and either stumbled on the right word or substituted a nonsense word. An example was substituting the word “ostrich” for “orchestra.” The substitution completely changed the meaning.

“Finally, the two other areas of concern involved the way that Jacob wrote, as well as his spelling. While Jacob could memorize for the spelling test, his spelling and his open ended-writing were very weak. The amount of effort that Jacob put into writing a small informal paragraph was considerable. There also wasn’t one sentence that was complete.”

“Even though Jacob is unlikely to be classified in special education, I think he has a learning disability that matches the definition of dyslexia as it is known clinically (see International Dyslexia Association website: www.ida.org ). The scores simply do not tell the story.”

“Dyslexia is not a score.”

Takeaway Point:

You need to look under the hood to see what’s going on with the engine. With dyslexia, you can’t just look at the scores and make a conclusion.

Great visual

“Learning Disablities’ movement turns 50

From THE WASHINGTON POST

by Valerie Strauss on April 12, 2013 at 4:00 am

It was 50 years ago this month that the movement to help students with learning disabilities began. Here’s what happened. This post was written by Jim Baucom, professor of education, has been teaching for more than a quarter of a century at Landmark College in Putney, Vermont.

It was 50 years ago this month that the movement to help students with learning disabilities began. Here’s what happened. This post was written by Jim Baucom, professor of education, has been teaching for more than a quarter of a century at Landmark College in Putney, Vermont.

By Jim Baucom

This month, we will commemorate an important historical event that opened doors for generations of students with learning differences and, in essence, may have made Landmark College, where I teach possible. At Landmark, we specialize in teaching students who learn differently, using methods designed specifically for those with dyslexia, ADHD and Autism Spectrum Disorders.

Fifty years ago, on April 6, 1963, a group of concerned parents convened a conference in Chicago to discuss a shared frustration: they all had children who were struggling in school, the cause of which was generally believed to be laziness, lack of intelligence, or just bad parenting. This group of parents knew better. They understood that their children were bright and just as eager to learn as any other child, but that they needed help and alternative teaching approaches to succeed in school.

One of the speakers at that conference was Dr. Samuel Kirk, a respected psychologist and eventual pioneer in the field of special education. In his speech, Kirk used the term “learning disabilities,” which he had coined a few months earlier, to describe the problems these children faced, even though he, himself, had a strong aversion to labels. The speech had a galvanizing effect on the parents. They asked Kirk if they could adopt the term “learning disabilities,” not only to describe their children but to give a name to a national organization they wanted to form. A few months later, the Association for Children with Learning Disabilities was formed, now known as the Learning Disabilities Association of America, still the largest and most influential organization of its kind.

These parents also asked Kirk to join their group and serve as a liaison to Washington, working for changes in legislation, educational practices, and social policy. Dr. Kirk agreed and, luckily, found a receptive audience in the White House. Perhaps because his own sister, Rosemary, suffered from a severe intellectual disability, President Kennedy named Kirk to head the new Federal Office of Education’s Division of Handicapped Children.

At the time of that historic meeting in Chicago, the most powerful force for change in America was the Civil Rights movement. Today, we would do well to remember that the quest for equal opportunity and rights for all was a driving force for those who desired the same opportunity for their children who learned differently.

Five months after the Chicago meeting, Martin Luther King Jr. led the march on Washington where he delivered his inspiring “I Have a Dream” speech. Twelve years later, The Education for All Handicapped Children Act was enacted, guaranteeing a free and appropriate education for all children.

Special services for students who learn differently began to flourish, giving those who had previously felt little hope an opportunity to learn and succeed in school.

The ripple effect kicked in, and these bright young people set their sights on college, a goal that would have been rare in 1963. This led to the historic founding of Landmark College 27 years ago, as the first college in the U.S. created specifically for students with learning differences.

In Lewis Carroll’s Through The Looking Glass, Humpty Dumpty emphatically declares: “When I use a word it means just what I choose it to mean – neither more nor less.” If only that were true of diagnostic categories, like “learning disabilities.” Our students are bright and creative learners who ultimately show no limitations in what they can achieve either academically or in their professional careers, so we prefer “learning differences.” It’s reassuring to know that even Dr. Kirk thought the term did not fully capture the capabilities and needs of these unique learners.

At our campus celebration, we won’t parse labels, or any other words for that matter. But instead, we will recognize the actions taken by a small group of concerned parents gathered in Chicago a half century ago who only wanted their children to receive a better education. Today, we call that advocacy and it’s worth celebrating.

Common Signs of Dysgraphia: Children Grade 3 – 8

From NCLD.org

|

Sally Gardner: Ten Tips for a Dyslexic Thinker (like me)

FROM THE TELEGRAPH

Award-winning author and illustrator Sally Gardner offers advice on dyslexia at the start of Dyslexia Awareness Week.

By Sally Gardner

6:45AM BST 08 Oct 2012

To coincide with Dyslexia Awareness Week (Monday 8th – Sunday 14th October), author Sally Gardner offers 10 tips for dyslexics.

• 1. Remember dyslexia comes in all shapes and sizes, so it cannot be swept over with a ‘one size fits all’ approach. Firmly ignore and disregard all humans who tell you it’s a disability and those who patronise you. Don’t give up on what interests you.

• 2. A good sense of humour is vital. Try not to take yourself too seriously, especially when you make a muddle up. Laughter is the best remedy. Remember too that non dyslexic thinkers can often make a muddle of the things we find easy to do.

• 3. Listen to audio books. I listen to at least two per month – dyslexia is not an excuse for not being well read – far from it.

• 4. Use a dyslexic font, there are several available online to buy and download. Find the one that works well for you. They are fab and finally for me, at least, it has stopped the B and the P getting muddled up.

• 5. I find writing in different colours very useful. I start the day in one colour, in the afternoon I use another and cut paste together before putting it all back to black. Double spacing and larger font is essential.

• 6. Try and learn joined up writing, what they call ‘handwriting’ at school. Even good spellers’ writing is illegible in this format and so you can get away with very bad spelling. If not sure which way round the ‘i’ or the ‘e’ goes, do a ‘u’ and dot the middle. BN. This only works with joined up writing.

• 7. Leave more than enough time if going for a job interview or other important meeting in case you’ve written the number of house or building etc. down wrong eg. 47 could be 74… Apparently there’s no excuse for being late – well, I think this is a reasonable one.

• 8. I keep a piece of soft sand paper which helps when learning how a word is spelt. Write it once to feel it on the sand paper, then write it again.

• 9. Holding a hand exercise squeeze ball, or something pliable like playdough, is very helpful for concentration. I find that if I read a page holding one, I remember much more than without it.

10. Remember you are unique. Every one of us on this plant has special needs. Spelling is just the tip of the iceberg – dyslexia is a way of thinking, a way of being, it is who you are. Be proud of yourself. After all most humans can read but we can make letters dance and much more besides. Dyslexia rules KO.

Dyslexia and the Old Masters: A brief look back

From

Dyslexia and the Old Masters: A brief look back

About a month or so ago I had the honor to present to a group of parents of dyslexic children on Staten Island. The group,Wishes of Literacy, is doing great work in their advocacy for parents and they are joining forces with the burgeoning grassroots Decoding Dyslexia movement, such as theDecoding Dyslexia NJ and Decoding Dyslexia NY groups.

Even though I’d to believe I know my stuff when it comes to the topic of dyslexia and reading disabilities, I did a little “homework” on the topic before the talk and I found myself reading about the history of dyslexia assessment and treatment.

What I have always appreciated was that there were many old masters, long forgotten giants in the field of reading research, who got it. They understood the issues. They knew what worked. What they said decades ago applies to the present day.

Here are a few choice quotes:

In 1909 James Hughes in his book “Teaching to Read” noted,

“Oral language being natural is learned without conscious effort. Visible language (i.e., reading) being artificial, has to be learned by a conscious effort.

“Word recognition is the only possible basis of reading…the best method of teaching word recognition is the one that makes the child independent of the teacher.”

That was in 1909!!!!!

Later in 1967 the late, great Dr. Jean Chall, stated:

“It would seem, at our present state of knowledge, that a code emphasis – one that combines control of words on spelling regularity, some direct teaching of letter-sound correspondences, as well as the use of writing, tracing, or typing – produces better results with beginners than a meaning (i.e., literature-based or comprehension) emphasis.”

Dr. Robert Dykstra said it well in 1974:

“We can summarize the results of 60 years of research dealing with beginning reading instruction by stating that early systematic instruction in phonics provides the child with the skills necessary to become an independent reader at an earlier than is likely if phonics instruction is delayed and less systematic.”

It is also important to remind ourselves that the Orton-Gillingham method has essentially gone unchanged since the 1930s. With all of the Orton-Gillingham methods out on the market currently, really what they represent are good old wine in fancy new bottles.

Takeaway Point:

While our research or “evidenced-based” window is very narrow looking back over a few years, there’s little new under the sun. The old masters in the field of reading research and dyslexia really knew their stuff.

The start of the school year is a busy time for students, parents and teachers alike. This guide will help you better advocate for the needs of your child with LD so she isn’t lost in the shuffle. Learn how – and why – to become an effective advocate and ally for your child with LD. From understanding your child’s disability and special education law, to managing your emotions, to communicating effectively, this guide covers it!

The start of the school year is a busy time for students, parents and teachers alike. This guide will help you better advocate for the needs of your child with LD so she isn’t lost in the shuffle. Learn how – and why – to become an effective advocate and ally for your child with LD. From understanding your child’s disability and special education law, to managing your emotions, to communicating effectively, this guide covers it!