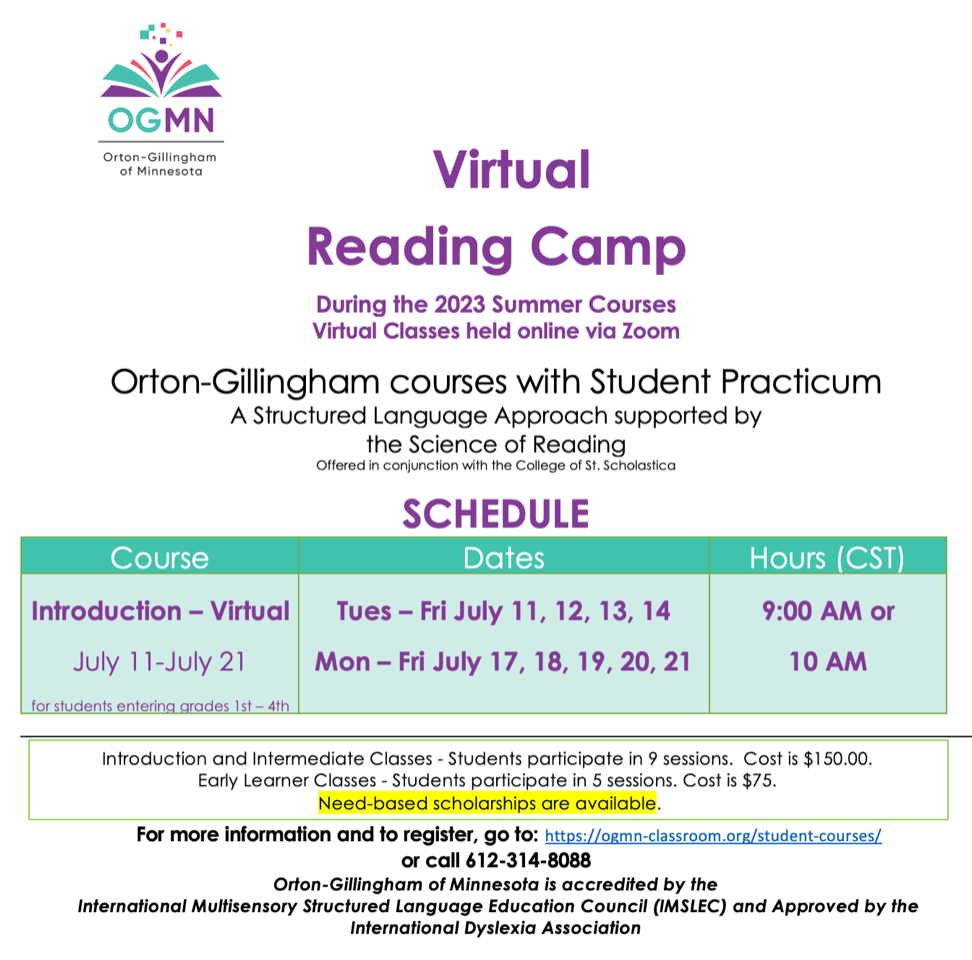

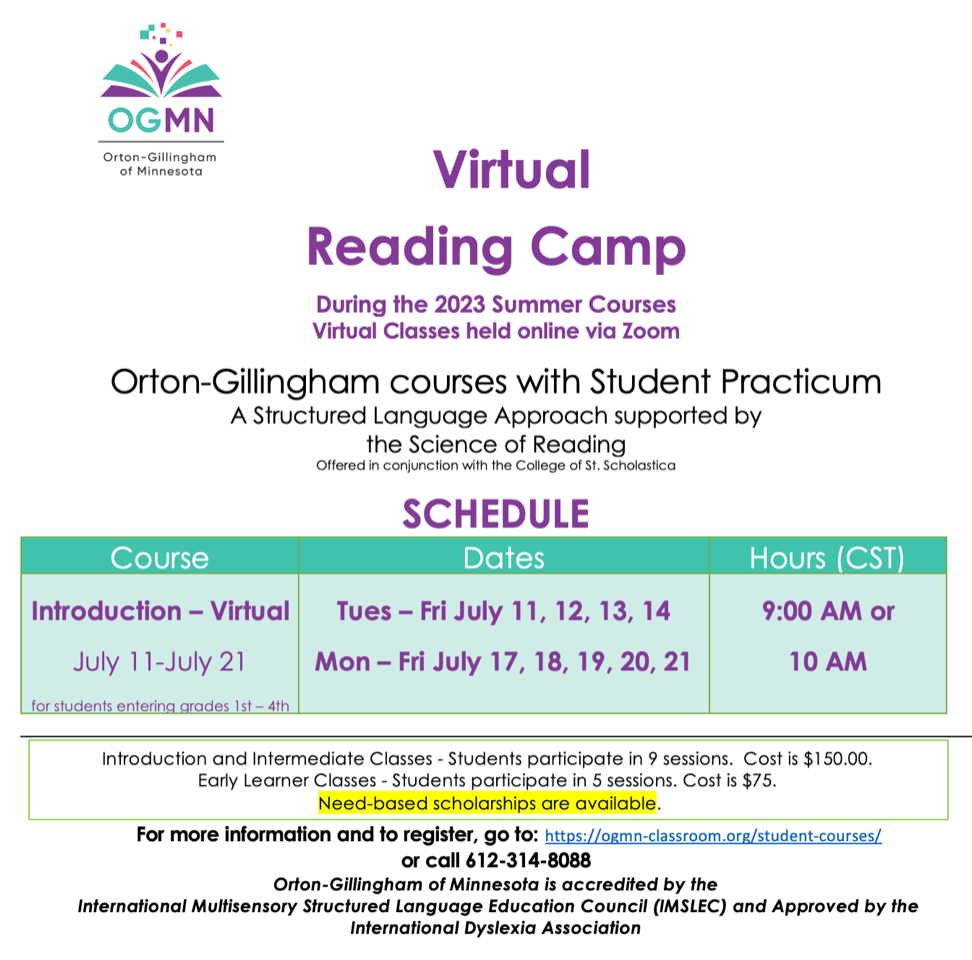

If you have any questions, please contact me directly at 218-340-7393 or [email protected]. Registration is available at the following link.

If you have any questions, please contact me directly at 218-340-7393 or [email protected]. Registration is available at the following link.

With the beginning of the New Year, many are looking for an uneventful year in 2021. However, the fallout of the Covid 19 pandemic needs us to look carefully at the reading progress of students. In order to close the reading gap, regardless of how it happened, we need to shift our focus on reading instruction that follows the Science of Reading. But what is the Science of Reading?

The Science of Reading is a body of scientific research that reaches across interdisciplinary teams and studies how reading and writing, which are complex human behaviors that are impacted by biological markers, are learned. The research has occurred over almost a century and continues to evolve around the world and the U.S. The research should inform teaching practices to help all students, and especially those that are struggling. Dr. Louisa Moats states “The body of work referred to as the ‘science of reading’ is not an ideology, a philosophy, a political agenda, a one-size-fits-all approach, a program of instruction, nor a specific component of instruction.”

If you want to learn more about the Science of Reading, consider joining one of the numerous Facebook pages.

‘Minnesota’s Science of Reading – What I should have learned in college’ which focuses on educators.

‘Science of Reading (SOR) Parents’ Group’ which is directed toward parents.

The ‘Science of Reading – Kindergarten/First Grade Discussion Group’ for Kindergarten & 1st-grade teachers,

or any of those managed by “The Reading League”, a non-profit organization out of NY.

Be healthy, happy, and at peace.

Mondays in January and February 2020

Space will be limited

DYSLEXIA SIMULATION – Jan 27 – An opportunity to glimpse into a struggling student’s classroom experience

Researchers estimate that in every student body population 5% of students struggle with dyscalculia, up to 6-10% struggle with dyspraxia, 12-17% struggle with dyslexia and up to 20% struggle with dysgraphia. After the simulation, we will discuss how it impacts school and learning for children.

DYSLEXIA – Feb 3 – Understanding the brain functions behind dyslexia, difficulty with reading, and what remediation should look like.

Dyslexia impacts approximately 12-17% of students along a continuum. The discussion includes learning strategies, remediation vs accommodations, social/emotional impact, assessments, 504 vs IEPs, and student empowerment.

DYSGRAPHIA – Feb 10 – Understanding the brain functions behind dysgraphia, the difficulty with handwriting and the final written product, and remediation.

Dysgraphia is often, but not always, a co-existing condition. We will discuss signs of dysgraphia, potential direct, explicit, systematic instruction, and possible accommodations. Brief information about dyspraxia and the role it may be playing.

DYSCALCULIA & DYSPRAXIA – Feb 24 – Understanding the brain functions behind dyscalculia, difficulty with math, and what remediation should look like.

Dyspraxia is a common disorder affecting fine and/or gross motor coordination. Dyspraxia / Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD) is often regarded as an umbrella term to cover motor coordination difficulties which impact overall planning and carrying out of movements in the right order in everyday situations. Dyspraxia often coexists with the other ‘dys’s’.

I loved so much of what Dr. Selznick said in the piece below.

“Let’s say you have a little child, perhaps five or six years of age. He doesn’t know how to swim, so you decide it’s time to give him lessons. What if the swim instructor said something like, “You know we have strict standards for six year olds and we have determined that they need to start swimming in the six foot water instead of the shallow end of the pool.” You would probably be heading for the exit as fast as you possibly can.

Let’s switch to a different activity – writing. Take young Franklin, age six, a first grade student who is showing signs of early struggling. Franklin knows a small number of sight words and he can write his name. In a somewhat discernible scribble, Frankin can write letters from A – Z. (Well, maybe he misses a couple of letters.)

On a recent report card, here’s what Franklin’s teacher stated about his writing:

Franklin requires adult assistance completing various writing tasks including writing narratives and informational texts.”

Narratives? Informational text?

Franklin could no sooner write, “I got a new puppy” or “We went to the zoo,” then put together a narrative.

What am I missing here? Why talk about narrative text when the child is in the equivalent of the three-foot water of the pool? Wouldn’t a better point on the report card say something like, “We are targeting Franklin’s awareness of simple sentences.”

To borrow another image, before playing pieces of music you need to learn how to play simple notes and simple chords. The same is true of writing. Before asking a child to write narratives or journals asking for connected information, he needs to master very simple sentences.

Increasingly, I am seeing children (especially the boys) who haven’t the foggiest idea how to express themselves in writing. They have no sense of sentence awareness or paragraph structure. The simple fact is that asking them to write a paragraph and to perform open-ended writing tasks such as “Write about your weekend,” may simply be too much. Asking them to do so is misguided, placing them in situations of sheer frustration.

Takeaway Point:

Keep talking to the teacher. Let her know that your child can’t do what he is being asked. Help to get him out of the deep end as quickly as possible.”

You can find the original article at

http://shutdownlearner.com/wri

Learn more about this opportunity for additional Summer reading education at the link below!

As always Dr. Richard Selznick has some important ideas, this time about struggling writers. Here is his recent blog.

Open-Ended writing is usually not difficult for children on the “smooth road,” the ones without the myriad of variables leading to school struggling.

For the “Smooth-Roaders” their sentences are complete and varied in style. There is flow to their written stories generated and logic in their paragraphs.

With open-ended writing, children are given some type of prompt, such as, “write about your favorite trip,” or “write about your weekend.”

It is open-ended, because it can go in any direction. The idea is that the children will tap into their creative selves and be able to express themselves on paper.

However, for those children on the rougher road, the ones with a variety of learning problems, open-ended writing is brutal on many levels.

Here’s an excerpt from a writing sample of an 8-year-old writing about his favorite vacation:

“Uurvl is a ghat pls for a sekal reris. At first jassit park miat besley but the seord time you go it is cool…..Evening no it’s the slisy rias in the park it goes with Dr. serrl! Thes saren is call serrl laanring. Lastly, I’ll talk about the qrslins. Tars go lef and rert and lef and rert and, you get the ideas. There are sehal rrenis why I love going to uurvl.”

Or there was the 9 year old who wrote a story to a picture that he had drawn:

“Once aqha time ther was a boy namd levi he lived in a hog house and it was so mosh fon. and he livel in lll borenrom lahe. And he had loss of frahs and naders. The End.”

In screenings of their cognitive and intellectual capabilities, both of these kids demonstrated at least average cognitive potential.

Neither child was classified or receiving any type of service or official accommodation under a 504 Plan.

When the parents questioned what they should do they were told by the school to “read to your child.” There was also the veiled suggestion of putting the child on medication, “even though we are not doctors.”

For these children, reading to them or medicating them will not accomplish much relative to their fundamental inability to write.

Continuing with any open-ended writing will be particularly problematic, as they have no concept of what a sentence is and their spelling is severely impacting their thought process.For them, the concept of what represents a basic sentence is not something they have been taught or internalized and they are in need of intense, focused remedial instruction,

I usually dwell in metaphors or basic images that help to put things to parents in down-to-earth terms.

The metaphor of taking them back to the shallow end of the pool is fully applicable. They need to spend a lot of time in the shallow end of the pool (writing simple and basic sentences) and then incrementally moving out beyond, one baby step at a time.

Instead of encouraging creativity and “write what you feel,” they need to practice at the most simplistic levels building on a logical sequence of one skill leading to another.

http://shutdownlearner.com/wri

Hard Words: Why Aren’t Our Kids Being Taught to Read? is an amazing podcast (and text) by Emily Hanford at APMreports (https://www.apmreports.org/

From Emily Gibbons at The Literacy Nest.

Seven Summer Reading Tips for Struggling Readers

When I think of summer vacation, I have visions of popsicles, playing in the sprinkler, lemonade stands, long summer evenings and lazy days reading in a hammock. As an educator, I know that for struggling readers, reading is often the last thing on their mind when they think of relaxation. But, I also worry about summer learning loss or “the summer slide”. On average, students lose one month of school learning during the summer vacation. For students with dyslexia, the loss is likely even greater and will be more time consuming for them to regain than their peers. However, children with dyslexia have worked very hard all school year long and should definitely make time for fun and play. Striking a balance is key.

Here are a few tips for keeping reading a part of a balanced summer:

1: Don’t stop tutoring

It is tempting to “take the summer off” from tutoring, but in many cases, summer is a good opportunity to increase the amount of one-on-one tutoring your child is getting in order help them take a leap forward. Work with your tutor to schedule a time that allows your child to do activities important to them. Perhaps first thing in the morning is easiest, so they don’t feel interrupted. Or maybe early evening after day camp is a better time. If they need a break, consider taking a week at the end of the school year and a week before the new school year starts to recharge, but continue tutoring during the rest of the summer.

2. Make friends with your Librarian

Your local library is one of the best summer resources around. Most have a summer reading incentive program and special summer programming with crafts and special guests. Work with your children’s librarian on helping your child reach their reading goal. Reading to them, listening to audiobooks (ear reading) and reading on their own should all be able to count toward the goal. Set aside a day each week to visit and check out books.

3. Make a routine

Make daily reading a part of your family’s routine. Reading to your child, having them read to you or having “Family Reading Time” (everyone puts down their phones and picks up a book at a certain time each day) all help to ensure that reading doesn’t fall by the wayside on busy summer days.

4. Anything counts

Don’t hesitate if your child wants to read easy books, comic books, or listen to audiobooks. All of these are going to help their development as a reader in different ways, and they all have value. Podcasts are another great way to expand vocabulary and broaden your child’s knowledge about different topics.

5. Go Thematic

One way to make reading a bit more exciting for summer is to tie in books to summer vacation plans. Are you going on a boating adventure? Read books about boating and pirates. Are you going hiking or camping? Wilderness and adventure stories might be just your cup of tea. Keeping busy in the garden? Dive into some nonfiction books about insects and plants. Traveling to Prince Edward Island? Anne of Green Gables would make a perfect accompaniment to your travels. If you are extra creative, you can even tie in games and activities for lots of thematic summer fun.

6: Write with a purpose

It isn’t just reading that benefits from practice over the summer. Writing and spelling need an opportunity to stay fresh as well. Making a grocery list, sending postcards or letters to friends and family, and keeping a journal of summer adventures are all good ways of writing with a genuine reason.

7: Use technology.

Apps like Nessy for phonics games, or Epic for audiobooks are fun literacy reinforcements that kids of many ages can enjoy. Epic offers a special deal for signing up in the summer, so be sure to check that out!

I hope you will make a place for books and reading this summer and keep your child’s learning fresh, so they can hit the ground running when a new school year begins. Along the way, I hope you have a lot of fun sharing books and making memories. Don’t forget to have a popsicle and play in the sprinkler! After all, that’s what summer’s all about for kids (of all ages)!

Article by Jacki Reinert, Psy.D.

As part of an assessment I recently asked 17- year-old near senior, Bethany, “Who wrote Hamlet?” Looking bewildered, she said, “I have no idea.”

Then, when asked to define the word “tranquil,” she could not further no guess. Bethany had no association to the word.

By the end of the assessment, it turned out that Bethany scored in the 16th%ile for word knowledge and the 9th % ile for fund of information and general knowledge.

In contrast, Bethany functioned somewhat above average on tasks that were nonverbal, like putting blocks together to make spatial patterns and while analyzing a series of visual patterns.

“I think I have ADD,” Bethany said to me.

“What tells you that,” I asked her.

“When I read my mind wanders. I have no idea what I am reading. In class I can’t follow what the teacher is saying and have no clue what they are discussing. It has to be ADD – I think I should be on meds. Most of my friends are on meds.”

I get that kind of thing a lot – kids thinking they should “be on meds.”

Even though Bethany may benefit from stimulant medication, what I do know is that one of the primary reasons Bethany does not pay attention in class or while reading is that she lacks what I call “hooks in the mental closet.”

We used to think of reading as a fundamentally one-direction process. In this model words would go from the page to the brain. Researchers in the 1980s and 1990s enlightened us that reading (and listening to class lectures) was more of a two-way, interactive process.

The fact is the more “hooks we have in our mental closet” (the researchers used different terminology, mind you), the better we comprehend what we are reading or understand what we are listening to.

These “hooks” also help us to pay attention. While medication may help Bethany focus, she still needs to be building in background knowledge and word awareness to try and overcome her sense of feeling lost.

In short, Bethany needs to build in more hooks.

There are plenty of books on the market that may be helpful such as, “Words You Should Know In High School: 1000 Essential Words To Build Vocabulary, Improve Standardized Test Scores, And Write Successful Papers.”

I can tell you with pretty good assurance that Bethany knew about 15 % of the essential 1000 words.

Even if Bethany practiced two words per day for a year, she would be in much better shape with the 720 new words (365 words X 2) for the year that she could learn.

There would be 720 new hooks in her mental closet!!!

Takeaway Point

Hooks in the mental closet matter and may explain some of the reason your child is not paying attention or adequately comprehending. Try and build them in any way you can.