Tag Archives: Dyslexia

Parents Advocating for Student Success in EDucation (PASSED)

Lunch Gathering

Wed. June 26, 2013

Vineyard Church ~ 1533 W. Arrowhead Rd ~ Duluth, MN 5581

This group meets monthly to share ideas and support one another. If your child struggled last year in school this may be a good opportunity to hear what others in our community are doing to ensure their children’s success in learning. Occasionally, a speaker joins the group to cover a specific topic. All families are welcome.

Vineyard Church offers a lunch for $5.00 made by the members of the congregation, or you’re welcome to bring your own. Lunch is served at noon until they run out.

We also have a monthly evening gathering at Barnes and Noble 7PM on Thursday, June 27, 2013 for those that can’t make a noon time.

Our lunch gatherings are usually the third Wednesday of the month (June is an exception) and the evening meetings are usually on the fourth Thursday of the month. Email dwyers@boreal.org if you’d like more information.

Dyslexia: More Than a Score

By Dr. Richard Selznick (http://www.drselz.com/blog)

Saturday, June 8, 2013

***Note: (This blog was published some time ago, but due to a problem with the website it needed to be reposted. It has been revised.)

I had the good fortune to recently take part on a panel during a symposium on dyslexia sponsored by the grassroots parenting group, Decoding Dyslexia: NJ. Dr. Sally Shaywitz, the author of “Overcoming Dyslexia” was the keynote speaker. While talking about assessing dyslexia, Dr. Shaywitz said something that really struck me. She noted, “Dyslexia is not a score.”

That statement is right on the money.

Scores are certainly involved in the assessment of dyslexia. Tests such as the Woodcock Reading Mastery Test, the Tests of Word Reading Efficiency and the Comprehensive Tests of Phonological Processing, among other standardized measures yield reliable and valid standard scores, grade equivalents and percentiles. These scores can be helpful markers. However, the scores often don’t tell the whole story.

Here’s one example:

Jacob, a fifth grader, is in the 80th%ile of verbal intelligence and his nonverbal score is in the 65% percentile, meaning Jacob’s a pretty bright kid. Jacob’s word identification standard score on the Woodcock was a 94 placing him solidly in the average range, with similar word attack and passage comprehensions scores. Effectively, both of the scores (Word Identification and Word Attack), placed Jacob just below the 50th percentile, but solidly in the average range.

Jacob’s scores would not have gotten the school too excited. Yet, here’s what I told the mom.

“There’s a lot of evidence in Jacob’s assessment that suggests that he is dyslexic. Even though his scores are fundamentally average, he was observed to be very inefficient in the way that he read. For example, while Jacob read words like “institute,” and “mechanic” correctly, he did so with a great deal of effort. It was hard for Jacob to figure out the words. For those who are not dyslexic, word reading is smooth and effortless. Those words would be a piece of cake for non-dyslexic fifth graders. They were not for Jacob.”

“Even more to the point, was the way that Jacob read passages out loud. Listening to Jacob read was almost painful. Every time he came upon a large word that was not all that common (such as, hysterical, pedestrian, departure) he hesitated a number of seconds and either stumbled on the right word or substituted a nonsense word. An example was substituting the word “ostrich” for “orchestra.” The substitution completely changed the meaning.

“Finally, the two other areas of concern involved the way that Jacob wrote, as well as his spelling. While Jacob could memorize for the spelling test, his spelling and his open ended-writing were very weak. The amount of effort that Jacob put into writing a small informal paragraph was considerable. There also wasn’t one sentence that was complete.”

“Even though Jacob is unlikely to be classified in special education, I think he has a learning disability that matches the definition of dyslexia as it is known clinically (see International Dyslexia Association website: www.ida.org ). The scores simply do not tell the story.”

“Dyslexia is not a score.”

Takeaway Point:

You need to look under the hood to see what’s going on with the engine. With dyslexia, you can’t just look at the scores and make a conclusion.

“Learning Disablities’ movement turns 50

From THE WASHINGTON POST

by Valerie Strauss on April 12, 2013 at 4:00 am

It was 50 years ago this month that the movement to help students with learning disabilities began. Here’s what happened. This post was written by Jim Baucom, professor of education, has been teaching for more than a quarter of a century at Landmark College in Putney, Vermont.

It was 50 years ago this month that the movement to help students with learning disabilities began. Here’s what happened. This post was written by Jim Baucom, professor of education, has been teaching for more than a quarter of a century at Landmark College in Putney, Vermont.

By Jim Baucom

This month, we will commemorate an important historical event that opened doors for generations of students with learning differences and, in essence, may have made Landmark College, where I teach possible. At Landmark, we specialize in teaching students who learn differently, using methods designed specifically for those with dyslexia, ADHD and Autism Spectrum Disorders.

Fifty years ago, on April 6, 1963, a group of concerned parents convened a conference in Chicago to discuss a shared frustration: they all had children who were struggling in school, the cause of which was generally believed to be laziness, lack of intelligence, or just bad parenting. This group of parents knew better. They understood that their children were bright and just as eager to learn as any other child, but that they needed help and alternative teaching approaches to succeed in school.

One of the speakers at that conference was Dr. Samuel Kirk, a respected psychologist and eventual pioneer in the field of special education. In his speech, Kirk used the term “learning disabilities,” which he had coined a few months earlier, to describe the problems these children faced, even though he, himself, had a strong aversion to labels. The speech had a galvanizing effect on the parents. They asked Kirk if they could adopt the term “learning disabilities,” not only to describe their children but to give a name to a national organization they wanted to form. A few months later, the Association for Children with Learning Disabilities was formed, now known as the Learning Disabilities Association of America, still the largest and most influential organization of its kind.

These parents also asked Kirk to join their group and serve as a liaison to Washington, working for changes in legislation, educational practices, and social policy. Dr. Kirk agreed and, luckily, found a receptive audience in the White House. Perhaps because his own sister, Rosemary, suffered from a severe intellectual disability, President Kennedy named Kirk to head the new Federal Office of Education’s Division of Handicapped Children.

At the time of that historic meeting in Chicago, the most powerful force for change in America was the Civil Rights movement. Today, we would do well to remember that the quest for equal opportunity and rights for all was a driving force for those who desired the same opportunity for their children who learned differently.

Five months after the Chicago meeting, Martin Luther King Jr. led the march on Washington where he delivered his inspiring “I Have a Dream” speech. Twelve years later, The Education for All Handicapped Children Act was enacted, guaranteeing a free and appropriate education for all children.

Special services for students who learn differently began to flourish, giving those who had previously felt little hope an opportunity to learn and succeed in school.

The ripple effect kicked in, and these bright young people set their sights on college, a goal that would have been rare in 1963. This led to the historic founding of Landmark College 27 years ago, as the first college in the U.S. created specifically for students with learning differences.

In Lewis Carroll’s Through The Looking Glass, Humpty Dumpty emphatically declares: “When I use a word it means just what I choose it to mean – neither more nor less.” If only that were true of diagnostic categories, like “learning disabilities.” Our students are bright and creative learners who ultimately show no limitations in what they can achieve either academically or in their professional careers, so we prefer “learning differences.” It’s reassuring to know that even Dr. Kirk thought the term did not fully capture the capabilities and needs of these unique learners.

At our campus celebration, we won’t parse labels, or any other words for that matter. But instead, we will recognize the actions taken by a small group of concerned parents gathered in Chicago a half century ago who only wanted their children to receive a better education. Today, we call that advocacy and it’s worth celebrating.

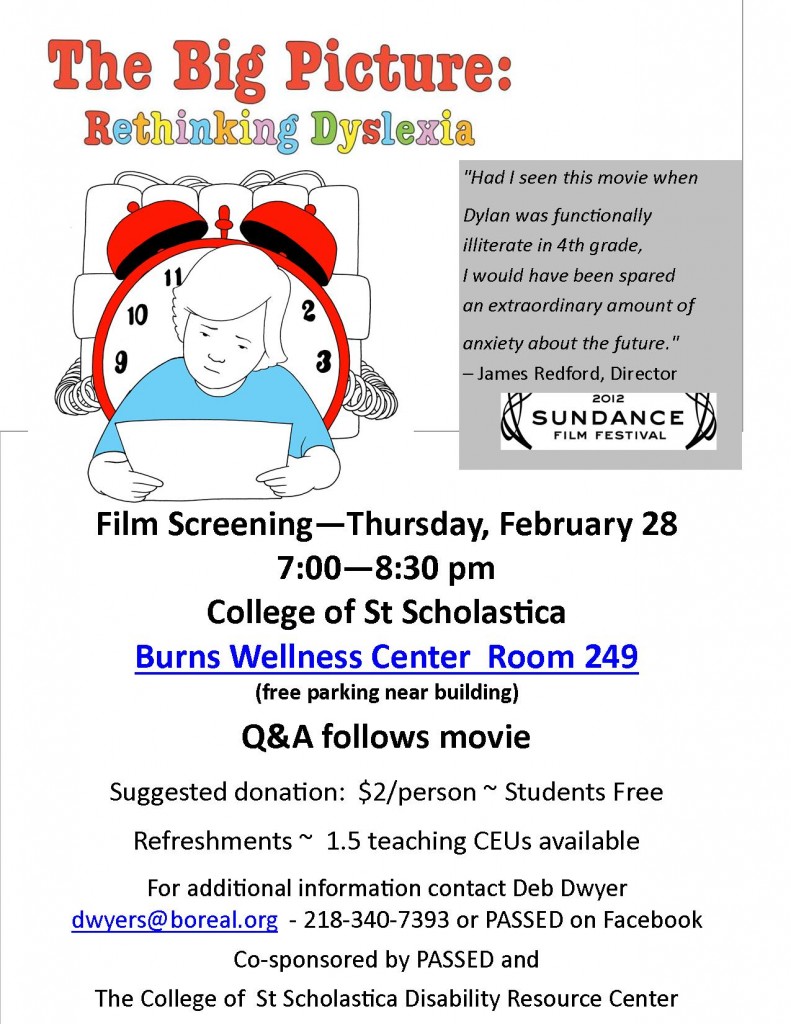

Thursday, Feb. 28, 2013

About

Why do I tutor?

My greatest passion is to help children succeed in reading and writing. I’ve been told I’m very good at it both from my students and their parents.

The Journey!

My daughter went to school and life was good, well at least academically.

My son went to school and I knew something was wrong. I even asked if they thought I should hold him back a year. No, he’s fine. And so the story went. In second grade, he was one of the teacher’s stronger readers – to my surprise. But when she told me what they were reading I realized that he had memorized them at home. They didn’t read one story that he had not had read to him multiple times. ….. In third grade, we started getting outside evaluations and found out he was dyslexic with a disorder of written expression. Then in fifth grade I was homeschooling him after little progress in the traditional school.

That was the year he learned to read. I wasn’t yet trained in Orton-Gillingham, but in hind site I used a lot of what I’ve learned about how to teach dyslexic students. The piece I was missing was how systematic it should be. This son is now 24 (2016), he graduated from Guilford College in Greensboro, North Carolina with honors in physics and mathematics. He is teaching in Louisville, KY with the Teach Kentucky Program. He received his Masters of Education from the University of Louisville, in May of 2016.

Then along came my baby who read all the time. His vocabulary was always years ahead of his peers. In third grade, he still hadn’t chosen a dominate hand. He couldn’t print his alphabet appropriately, so how would he learn to write cursive (his teacher agreed with me). Even though he couldn’t put anything on paper his teacher called him “Fantasy Boy” because of the great stories he created orally. His writing only got worse, yet his reading comprehension remained grades ahead. Middle school was so difficult for him, he would come home and take multiple baths to relax. He did some occupational therapy which helped with some things, but not really with the writing process. I decided to homeschool him for eighth grade (a downward spiral was happening at school). This gave us time for more outside testing and interventions. Oh! Surprise (sarcasm), he had a disorder of written expression (dysgraphia). By now, I was noticing that even though his comprehension was so high he was making odd mistakes when he read out loud. Some fabulous people have helped us along this journey. As a junior in high school, he enrolled in college through PSEO (Post Secondary Enrollment Option) and carried a full load of courses. He graduated from high school in 2013 with 60 plus college credits. He is scheduled to graduate from University of MN, Duluth in 2017, with lots of educational experiences along the way.

Both of my boys are twice exceptional, which means they are gifted with a learning disability. So qualifying for services in school seemed to be a completely different process. They both ended up with a 504 plan. But this path of the journey was full of disappointments in a system I believed was meant to educate children. That is a story for some other day.

I was fortunate enough to volunteer in the schools while my children were growing up and still do. I was always asked to help those that had difficulties. I knew what students at a given age were capable of doing in school.

My training in Orton-Gillingham has given me the training and tools I wish I’d had when my boys were younger. My greatest passion is to help children succeed. References are available.

Struggling students and Response to Intervention (RTI)

Parent Rights in the Era of RTI

If a school is using an RTI approach, what rights do parents have and what strategies can be used to address identification issues?

If a school is using an RTI approach, what rights do parents have and what strategies can be used to address identification issues?

- RTI Use across States—The manner in which states incorporate RTI into SLD identification varies dramatically.

- Child Find—Your school district’s legal obligation to “find” all children who may have a disability and, because of their disability, need special education services.

- Rights to Evaluation—Every parent has the right to request an evaluation at any time to determine if their child has a disability and what that child’s educational needs are.

- Strategies for Addressing Identification Issues—The process of determining whether your child has a disability such as a learning disability and needs special education cannot go on indefinite l

The above is from

For a free booklet on additional information go to http://info.ncld.org/parent-rights-in-the-era-of-rti

Conversation about Dyslexia

6:00 PM at Barnes and Noble at the Miller Hill Mall in Duluth, MN, on Tuesday, October22. Conversation will be driven by the participants that attend. Topics that are expected to be discussed are signs of dyslexia, potential classroom accommodations, informal assessment verses comprehensive educational evaluation, assistive technology, and more.

Dyslexia in the Classroom

Article from The Portland Press Herald in Maine

Maine Voices: As schools start, it is important to identify dyslexia early

Though dyslexia is not curable, proper instruction makes a big difference in helping affected children.

By JULIE BOESKY

Did you know that there are at least 40,000 children in Maine with dyslexia?

40,000!

If we include adults, there are at least 200,000 Mainers affected by the same condition.

Affecting roughly 15 percent of the general population and often running in families, dyslexia is widely misunderstood and profoundly impacts learning, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the National Center for Learning Disabilities.

In a typical school serving 500 children, that translates to roughly 75 dyslexic students exhibiting varying degrees of reading difficulties ranging from mild to severe.

For a variety of reasons, many of these students may not be identified in the special education system.

As Maine children head back to school, we all share the hope that it will be a successful year. We cannot leave this 15 percent of our children out of the equation.

It is a particularly compelling time of year to ask the question: Is your child or student dyslexic? Do you know what signs to look for?

First and foremost, dyslexia is a well-understood, clearly defined condition.

If someone tells you that dyslexia does not exist or “went out of style,” run, don’t walk, to a more accurate source.

Second, dyslexics are not unintelligent. On the contrary, many dyslexics are highly intelligent, often demonstrating particularly strong artistic skills and strengths in problem solving.

Dyslexics do not “see words backwards.”

They often have difficulty accurately reading or pronouncing words that look similar.

Dyslexics often intend to say one word but say another.

Dyslexia is not the result of laziness and it cannot be “cured.”

It is the result of a common neurological variation in the way the brain processes print information that can make it extremely difficult to read quickly and accurately, and also makes spelling more difficult.

Not surprisingly, this condition often profoundly impacts a dyslexic child’s performance in school and can be devastating to his or her self-esteem without proper support.

Teachers and parents should be on the lookout for children who have consistent difficulty recognizing and responding to simple rhymes, sounding out short words, or remembering letter names.

Some of these early signs of dyslexia, such as difficulty with rhyming, can be identified before a child even begins kindergarten, and shouldn’t be dismissed as “something he’ll grow out of.”

Teachers must be aware of the significant number of dyslexic children that pass through their classrooms each year.

In a typical classroom of 20 students, statistics tell us that at least three of those students will be dyslexic.

While all children benefit from clear, direct instruction in reading, it is especially important that dyslexic children get the right kind of reading instruction as early and intensively as possible.

Dyslexia is not “curable” or something to be “fixed,” but proper instruction makes a tremendous difference in helping affected children learn to read and be successful in school.

The earlier the learning difference is discovered, the sooner a child can receive the help that he or she needs.

Perhaps even more important, parents and teachers can help a child to understand that he is not “stupid” or “lazy,” nor alone, but that he has a common variation in how he learns and will need extra patience and practice with reading.

A number of studies have clinically proven that the risk to a child of low self esteem stemming from dyslexia can be successfully countered by arming the child with age appropriate, accurate information about what dyslexia is and is not so that he can learn from an early age how to best advocate for his own learning.

In the Portland area, the Maine Twig/ New Hampshire. Branch of the International Dyslexia Association offers a free monthly support group for parents of struggling readers. It is held at the Portland Public Library at noon on the third Friday of each month (resuming Sept. 21).

The Children’s Dyslexia Center in Portland, usually full well beyond capacity, offers tutoring services for dyslexics as well as instructional training for adults.

Many wonderful resources are also available now on the Internet for educators and families needing more information.

As we welcome our children back to school this fall, please help spread the word that dyslexia is not a strange or rare phenomenon.

It is a common learning difference impacting a significant percentage of our population that deserves far greater attention and accommodation so that we can expand literacy opportunities for all Mainers.

Julie Boesky is a member of the Maine/New Hampshire branch of International Dyslexia Association.

School is just around the corner…

With school just around the corner, it’s time to reread your children’s IEP or 504. Could a 504 with appropriate accommodations make for a more successful year? The following is from NCLD.org by Laura Kaloe, NCLD Public Policy Director

Is a 504 Plan Right for My Child? |

- The child has an identified learning disability (LD) or Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (AD/HD) but does not meet the requirements of IDEA for special education services and supports

- The child is currently receiving informal accommodations or ongoing support at school

504 Option: When Your Child Does Not Meet the Requirements of IDEA

The IDEA law requires that your child must meet two prongs of the law in order to be served by special education:

- the child must have one (or more) of the 13 disabilities listed in IDEA which includes learning disabilities and attention disorders; and,

- as a result of the disability, the child needs special education to make progress in school in order to benefit from the general education program.

This legal requirement essentially says that some kids with LD or AD/HD may not meet the state or district requirementsof the second prong. While the student may have a disability, it may not be impacting their learning in ways that qualify them for special education services. These students however, because they have an LD or AD/HD, may meet the requirement to have a 504 plan if their disability “substantially limits them in performing one or more major life activity.”

| Effective January 2009, eligibility for protection under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act became broader. Some students who did not qualify in the past may now qualify for Section 504 plans. Students with Section 504 plans may now qualify for additional supports, services, auxiliary aids, and/or accommodations in public schools.disabilities.For the rest of the article visit ncld.org and search 504 plans. |